School protects legal right to protest

When news of Canyon High’s walkout broke, Facebook erupted with misunderstanding.

“These kids just want a day out of school, they aren’t doing this out of respect for anyone or anything.”

“Most of the students can’t vote and should be worried about school not politics.”

“This is disgraceful.”

“This is not the CHS I graduated from.”

“I hope no student walks out.”

“Anything to get out of class.”

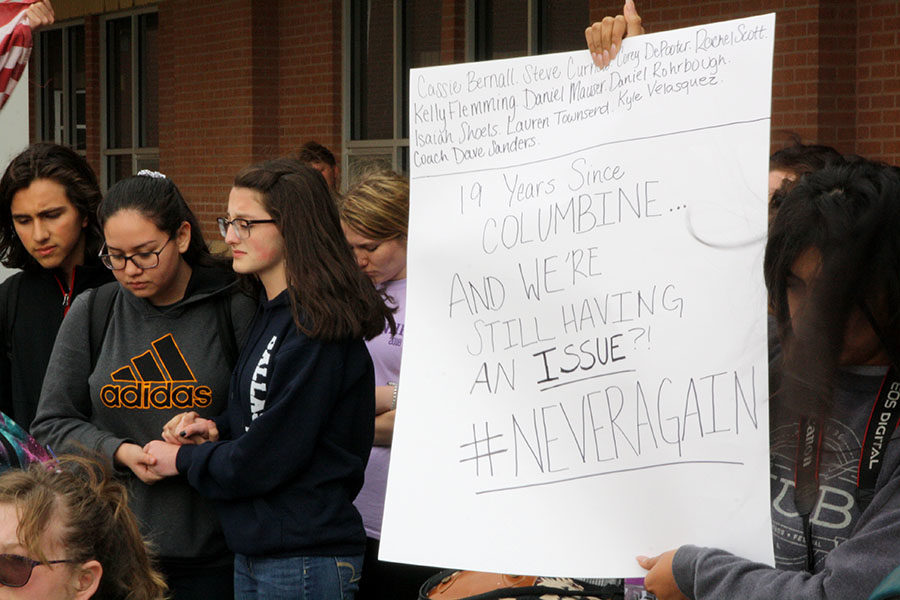

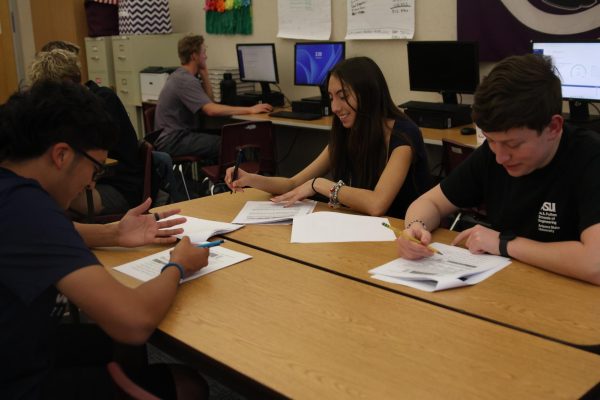

On April 20, 2018, students across America walked out of class to promote preventing gun violence and to honor the students killed in school shootings. Approximately 25 students from Canyon High decided to participate by organizing a local chapter of the national movement.

The original plan consisted of walking out the front doors, but Principal Tim Gilliland and student organizers came to an agreement: students could walk out into the breezeway during activity period, a half-hour dedicated to club meetings, tutoring, pep rallies and other activities. The compromise allowed students to participate without missing classes or disrupting school while staying safe.

The students did not plan the event for April 20 as an excuse to skip class and smoke marijuana, despite the coincidence. The date was set because of the Columbine school shooting on April 20, 1999.

CISD administration did not organize the event. Because the walk out did not affect the educational process, students were legally allowed to participate freely without consequence, unless they were late to third period. Students may do so because of the ruling from the Supreme Court in the “Tinker v. Des Moines” case.

In Dec. 1965, in the midst of the Vietnam War debate, a group of students, including 13-year-old Mary Beth Tinker, planned to wear black armbands to school in protest of the war. After the school board discovered the plan, they made an announcement that any student wearing the armbands at school must remove it and faced suspension for non-compliance. Tinker and four other students were asked to leave school for not removing their armbands and not return until the planned end of the protest. When they did return, it was in all black clothing in continued protest.

With parental help, the students sued the school district for violating the students’ right of expression, but the case was dismissed. Eventually, the case advanced to the Supreme Court. On Feb. 24, 1969, the court ruled 7-2 students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” School officials cannot legally prohibit students from protesting or expressing their opinions unless it is a substantial disruption to school.

Judging from comments from various social media sites, many in the Canyon community are unhappy with the students’ decisions to walk out. However, it is just that–the student’s decision. The students made a choice to participate or not. Even though focus was on the main protest, another started a counterprotest consisting of approximately eight students. Despite backlash from the original protest, students voiced their opinions. They made a choice.

The school did not force students to walk out. The school did not plan the walkout. The students did not disrupt school. They decided to voice their opinions.

The administration of CHS has demonstrated they understand not everyone agrees politically, but they understand the importance of allowing students the right to express their opinions peacefully. With any walkout open to all students, there will be those who will go with the flow, who don’t really care about the issues, but many of the students feel strongly about political matters and are well versed in the issues. We are young, but the Supreme Court agrees time and time again, age does not negate protection under the First Amendment.

Hi there! I am a senior, and this is my third year on staff and second as editor-in-chief. I am choir president and a member of the varsity and show choirs, and in theater, I participate in musical and the One-Act Play competition. I am a self-proclaimed...

Hey there, I’m John Flatt, the video editor for The Eagle's Tale. I play the alto saxophone in the band, I’m an Eagle Scout, and I’m looking forward to spending this year with all my friends here on the newspaper staff. I hope to entertain and...

Pamela Young • Apr 22, 2018 at 4:34 am

Our United States Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights are we, the American people’s rights. Communication is always the key to success! The solution is simple….REMOVE the “Gun Free Zone” signs from all school campuses and GOOD Guys with guns STOP bad guys with guns! It’s just that simple!

Jill Ludington • Apr 21, 2018 at 7:55 am

Proud of the youth for taking a stand and voicing their beliefs despite some public opinion. This in no way affected their time in the classroom and collaboration took place. This makes me proud to know my children attend CISD.

Greg Lehnick • Apr 20, 2018 at 7:16 pm

It is imperative that we unite as a caring society to resolve the violence in our schools, and in our nation as a whole. The problem seems to be finding that common ground that we can work together to resolve. I fully support discussions on how to eliminate the violence in schools but find no rationale to focus only on the gun. The violence ending in the use of guns, or any other weapon, would seem to be a symptom of a bigger problem. As long as we see the problems in any area of our society and jump to the conclusion that I know how to solve your problem we lose the ability to unite. I don’t feel the gun is the problem but the hearts of all of us in this great nation.

Brenda Walsh • Apr 20, 2018 at 7:11 pm

Good for you, Eagles. I’m proud of you for taking a stand, and I’m equally proud of the administration for supporting these students’ right to protest.

Erin Taylor • Apr 20, 2018 at 4:37 pm

I am proud of how this was put together and executed. Thought and agreement between the students was met and it took place during the activity period. Students should not have to worry about their safety at school. These young people are learning how to voice their opinions and be heard and they are doing it without violence or trouble. I am a proud parent.

The speech given during the walk out was well written. Kudos!

Dave Yirak • Apr 20, 2018 at 1:38 pm

I am so proud of the students who excercised their first amendment rights of free speech and peaceful assembly. Gun violence at our schools has to end. How this is accomplished will take people openly discussing and searching for answers and acting to the benefit of our citizens. It is a complex issue that needs a non partisan solution. Now is the time to act. Let your voice be heard!

Kimberly Sharber • Apr 20, 2018 at 12:40 pm

Beautifully written article. Thank you for putting ALL the information out there, and quickly!